History can be a fascinating topic. Personal family history, particularly in the case of German families, bearing the historical legacy and burden of the Second World War, can be even more so.

My brother, who continues to be a great source of story ideas, came across an interesting German multi-media artist and photographer by the name of Susanne Schleyer, who had recently published a book called “Unterwegs” (“On the Road”), that includes photos of 12 world cities that she had visited, that were used as an inspiration for stories written by well-known German authors.

From 1994 to 2004 Susanne, together with her artist partner Michael J. Stephan, created an extensive project called “Trilogie” in which they confront German history in a very personal way. All three components of Trilogie use large-scale and regular size photos along with sound collages and interview sequences.

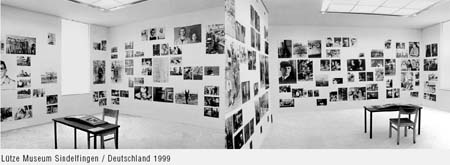

Part 1, “Asservate” (“Exhibits”) includes 160 black and white photos, sound recordings and a table and a chair. It illustrates 3 generations of German men in 3 different societies: After finding out about her grandfather’s role during Nazi Germany, Susanne created a three-dimensional photo album portraying her grandfather, representing the Nazi years; her father, who grew up in the former Communist East Germany; and her brother, who represents a modern reunified Germany.

Part 2 of Trilogie is called “Bueno!” and encompasses 449 photos and 23 oversize images with sound recordings. Susanne and Michael travelled to Buenos Aires to research and portray the German emigrant community: Germans that emigrated to Argentina before, during and after World War II, including a motley collection of Jewish refugees and Nazi perpetrators. While Asservate drew on German photo albums, Bueno! was produced directly on-site in present day Argentina. What in Europe had become a far away past, was preserved and upheld at the other end of the world – German history shock-frozen in the past.

Part 3 of the trilogy, entitled “Sologubowka”, encompasses 8 tableaux with 130 large-scale black and white photos, examining Nazi Germany’s invasion of Russia in the context of the consecration of Europe’s largest war cemetery, housing thousands of German WWII soldiers, which stands in stark contrast to the one single symbolic grave, representing the almost one million victims of the Leningrad Blockade when the Nazis held Leningrad under siege for 900 days. This exhibition has a definite political edge to it.

As the daughter of an Austrian nazi who faught in World War II, who never talked about his past and has now been dead for more than 10 years, I have a bit of envy in light of the fact that my name-sake Susanne Schleyer has actually been able to find out about her family’s history. She knows what her grandfather was involved in, whereas to this day I am still in the dark about my father’s past.

Here you can read this fascinating story about a modern-day German artist who has had the courage to confront her own personal and her national history.

1. Please tell us about yourself and your background.

I am from a small town in the German province of Thuringia [in former East Germany] and have been living in Berlin since age 18. I studied arts and German philology and later took an artistic photography degree in Leizpig. As an artist and photographer I live and work together with the artist Michael J. Stephan.

2. In the context of your art photography projects you have travelled a lot. Please tell us about the countries and cities that you have seen.

Because of our projects we had to travel a great deal since they were conceptual works which are implemented using images, text and sound. In order to take the pictures and to record the sound you have to travel to real locations. It would take to long to list all the cities and countries, but we have traveled all over North America, South America and Europe.

3. Please tell us about your recently published book „Unterwegs“ („On the Road“). How did you get the idea for it, how did you realize that idea?

During our travels for the various projects photos came about that were outside of our ideas. These were very narrative photos describing daily life in the various countries or cities. That’s how I got the idea of creating a book about twelve metropolitan cities: Berlin, Prague, Amsterdam, San Francisco, Buenos Aires, Saint Petersburg, Vienna, Amerstam, Rome, Venice, London and Paris. I gave these images to twelve very well-known young German authors and asked them to write stories for the photos. This was the opposite of the way it is usually done where normally visual artists always illustrate texts that have already been written.

The only condition was that these authors had already travelled to these cities before. In their stories they had to hook themselves into 2 or 3 photos and describe details of the photos. This resulted in very interesting combinations. Stories that entertain. Stories of murder, stories of love, detective stories etc.

4. Together with Michael J. Stephan you created a large-scale project with the title Trilogie. What triggered this project?

It is a matter of course for us artists that we make political statements. Art for the pure sake of art does not interest us. At the beginning of our work on Trilogie (1994) there was a time in Germany where the historical and sociological processing of the Third Reich had progressed a great deal. However, we, as the grand children of this generation, were not told anything about the daily life and the daily circumstances of how things could have developed into this situation. Even in artistic projects abstract statements were made. People spoke in the third person or of “other people”. When I decided to say “I” (use the first person) in the project Asservate (“Exhibits”, part one of the trilogy) and to connect German history with my own family, I encountered a great lack of understanding.

I don’t mean rejection, but people were simply not used to make personal references to the Third Reich. Today this is totally different. Many young authors and creative artists use their families’ stories in their work. This trend began at the end of the 1990s and continues today.

5. Please tell us in detail about the project „Asservate“ (“Exhibits”). What does it consist of, how did you execute it?

Much more often than one could guess through official reports or familiar conversations, we encounter in daily life and in the history of Germany a phenomenon that is the topic of the project “Asservate”. It deals with the question of how children and grand-children of Nazis live with their inherited “burden, the burden of the past.

In the families there is much silence or denial. It was rather late that I found out about the involvements of my grandfather with the NS regime. 1994 I then decided to research the past of my family in detail, and to process it through photos. A kind of walk-through family album had materialized from the extensive collection of materials. A personal family story/history was created that is prototypical for a large part of German families. The photo materials of my grandfather that I found are the basis for the project. I juxtapose the material of the son (my father) and the grandchild (my brother). The merciless banality, the routine processes quickly lead to a usual daily routine, even after the historic catastrophe. Life goes on, only the algebraic signs change, so to speak.