By Bruce Bell

Bruce Bell is the history columnist for the Bulletin, Canada’s largest community newspaper. He sits on the board of the Town of York Historical Society and is the author of two books ‘Amazing Tales of St. Lawrence Neighbourhood’ and ‘TORONTO: A Pictorial Celebration’. He is also the Official Tour Guide of St Lawrence Market. For more info visit brucebelltours.com

The building on the southeast corner of Sherbourne and Adelaide exists today because it had the fortitude to adapt to the times. Or, it was just plain lucky.

At present it’s totally unrecognizable but underneath all that red paint and patchy brickwork sits a fine Georgian house first built in 1842 by blacksmith extrordinare, Paul Bishop.

He built his house upon the foundations of one of the most famous manor homes of old York and consequently it now occupies some of the most historic land in the city. Paul Bishop’s house went on to miraculously survive the Great Fire of 1849, the onslaught of the Industrial Revolution and the horrors of the 1960’s Urban Renewal. Now thanks to Camrost-Felcorp Developers who have assured me that this historic house will be restored back to its early 19th century splendor as part of their new development of the north east section of King and Sherbourne to be known as Kings Court.

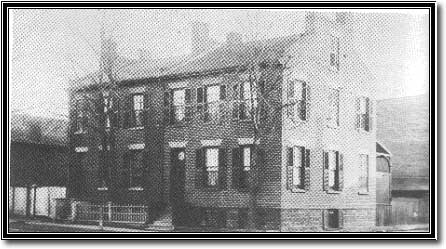

Paul Bishop’s House 1860

In 1793, the year of our European founding, what was to become the south east corner of Sherbourne and Adelaide was still part of a great forest. There was a small stream running into Lake Ontario which then came up as far as Front Street and the only buildings in the area were a few canvas and wooden huts hastily set up by the Queens Rangers in preparation of Gov. Simcoe’s arrival. In 1798 one of those Queens Rangers, William Jarvis, having liked this corner of the new capital of Upper Canada, now called York, so much that he built a small villa on what would become the four corners of Sherbourne and Adelaide and named it Jarvis House after himself, naturally.

The house built of squared logs was 30 by 41 feet had 2 floors and was covered with clap-boarding. The only major exterior detailing being a fanlight over the front door. William, the Provincial Secretary and Registrar from before Simcoe’s arrival in 1793 until his death in 1818, decided not to spend too much money on the outside in case he was forced to sell if the capital was to move to London.

The house sat on 2 acres spread over the entire Sherbourne and Adelaide area. The estate held 2 barns, a root-house, a stable, a chicken coup and, like the rest of our well to do founding fathers, had slave quarters built to house the six people he owned.

After William Jarvis died in 1817 his son cut the house and grounds into smaller sections. The house itself was taken over by a man named Lee who turned it into a restaurant and billiard room and added a small addition. In 1821 James Padfield rented a portion of the building and started a school.

Paul Bishop’s House today

When the school was disbanded in 1824, Isaac Columbus took possession of the property and converted one part into workshops and the rest into his home.

Isaac, a native of France, made swords and guns for our side during the War of 1812 at his forge near Fort York. Described as a ‘real character’ by 19th century historian Henry Scadding, he remembers telling Columbus that a specific item must be ready by a particular hour. Columbus staring him down with a terrifying glare reminded Scadding that only the King of France can use the term ‘must’.

Isaac hated the liberals of early Toronto because he believed that modern ideas ‘hindered the King from acting as a good father to his people’. In 1832 Isaac moves out and James Kidd moves in. It was during this time that the Jarvis House, as it was still known, became famous for unearthly reasons.

During the Cholera epidemics of the 1830’s several people died in the house including a few by suicide. Room after room wase now being sealed shut to prevent its spread. Townsfolk began to talk. ‘There’s something not right at the old Jarvis House’.

One dark and stormy night Mr. Kidd hears unnatural noises coming from Secretary Jarvis office, boarded up ever since it was believed to be haunted. So with a pistol in one hand, a crow bar in the other and lightning striking a ghostly silhouette upon the wall, James Kidd begins to pry open the door, but as he does the noises stop.

In an age when Frankenstein-the novel was a huge hit stories like this had a life all their own. A few days later a man by the name of Baxter arrives to spend the night at Jarvis house. Mr. Kidd hoping to solve the mystery assigned Baxter the haunted room.

During the night, it is recorded that ‘sounds of fury and noises never heard on this earth’ emanated from the haunted room. The next morning a haggard Mr. Baxter appears at breakfast with suitcase in hand telling all present “I will never pass another night in that room, let alone this house, Good day”. Some believed the apparition might have been that of John Ridout who was shot and killed in a duel by Samuel Jarvis, son of William, in 1817. To this day many believe his spirit, whose family had an estate next door, still floats about the Sherbourne and Adelaide area in search of his grave. Oh yea I forgot to tell you, both families had private burial grounds in their back yards.

In 1842 James Kidd sells the house to Paul Bishop on the condition that he be allowed to live there until he dies. He dies a year later and in 1848 Paul Bishop tears down the old Jarvis house and builds upon the foundations the structure that still stands, in part, today.

Bishop, a French Canadian whose real name L’Eveque meaning ‘the Bishop’ was Anglicized upon his arrival in Upper Canada, established himself as a 1st class blacksmith, locksmith and wheel maker, was also the son in law of previous owner Isaac Columbus. Before taking ownership Bishop had his workshop across the street on the northeast corner (today the site of the Jazz giant Montreal Bistro) where in 1837 something truly historic happen.

A few years before in 1834, the year of incorporation, Thornton Blackburn came from the United States and found employment working as a waiter in Osgoode Hall. In 1837 and always the inventive sort, Mr. Blackburn took a pattern of a horse drawn taxicab known then only to Montreal and London UK to Paul Bishops workshop. It was there in his shed that Mr. Bishop built for Mr. Blackburn the first horse drawn taxicab in Upper Canada. At a time when the United States, the land of the free-home of the brave, were still torturing and enslaving a tenth of their population, we here in Toronto had as our first taxicab owner a run-away American slave. The foundations of the house that Thornton and his wife Lucie lived in for over 50 years on Eastern Ave near Cherry street which served as a stop on the Underground railroad have been recently been found and preserved.

In 1860 Paul Bishop, having built the house he lived in for almost 30 years, left town and disappeared from our history books. The house then came under the possession of Thomas Dennie Harris. In his time he was one of leading merchants of the city, chief engineer of the fire brigade from 1838 to 1841 and harbour master from 1870 to 1872. Between 1841 and 1864 he was a warden of St. James’ Church. Harris owned a hardware store since 1829 around the corner at 124 King east, but it was destroyed during the Great Fire of 1849. Harris died in 1872 and with the encroachment of the Industrial Revolution upon this end of town the end was near for his home too. The small yard and fence that surrounded the house were torn up, as were the trees. Ironic because as warden of St. James one of Mr. Harris’s duties was to protect the poplar trees that surrounded the church at the time.

The great estates of the neighbourhood like the massive Moss Park (a story unto itself) up the street, the Ridout homestead next door and Russell Abbey down the street were being divided up and eventually demolished.

The area once part of a great forest was to become for the next 100 years a polluted industrialized zone. The historic house at Sherbourne and Adelaide was stripped bare of its interior ornamentation, it’s windows bricked up, new doors were smashed through, its chimneys the very essence of its Georgian appeal though still standing were built upon and the grand memories of its former days just faded away. For the next 10 decades it became everything from a machine shop to a garage to a flophouse. But it still stands and unlike its neighbours will return from the ashes to remind us all of our glorious past.